The Unfinished Puzzle of Unifying Relativity and Quantum Theory

Modern physics stands on two monumental pillars – General Relativity (GR) and Quantum Field Theory (QFT) – yet these frameworks remain stubbornly incompatible at a fundamental level. General Relativity portrays gravity as the smooth warping of a continuous spacetime fabric, whereas quantum theory insists that forces and fields come in discrete quanta. In other words, GR and QFT have opposite views on the continuum vs. the discrete. Attempts to force them into a single mathematical edifice – a theory of “quantum gravity” – have encountered deep conceptual roadblocks.

Why is unification so hard? Part of the trouble is that each theory relies on idealized simplifications about reality. General Relativity treats spacetime as an infinitely smooth continuum, ignoring any quantum ‘grain’ it might have at microscopic scales. QFT, on the other hand, is built on the idea that fields are quantized into countable particles or excitations. Each framework “boxes” the world into certain assumed categories (smooth geometry for GR, particle-like quanta for QFT), and each works astoundingly well in its own domain. But when gravity gets ultrahigh in energy or quantum effects become significant over cosmic distances, our separate models break down. Neither theory by itself can describe, for example, what happens inside a black hole or at the Big Bang. Decades of effort in quantum gravity (from string theory to loop quantum gravity) have not yet produced a clear resolution, suggesting that our current conceptual tools might be part of the problem.

Notably, one fundamental clash is over the nature of spacetime itself: is it continuous or discrete? General Relativity’s mathematics assumes a smooth continuum, while many quantum gravity approaches predict that spacetime has an ultimate “graininess” (a smallest unit, like the Planck length). Yet even this binary framing could be misleading. Recent reflections in physics and philosophy propose a more subtle answer: perhaps nature is neither simply continuous nor simply discrete, but something beyond those categories. We will explore this provocative idea later on. First, let’s examine how even our most successful theories – quantum physics itself – rely on discrete assumptions that may only be approximations of a deeper reality.

Physics Through a Discrete Lens: Particles, Fields, and Forces

Both quantum theory and the Standard Model of particle physics achieve their predictive power by carving the world at its seams – or at least, at seams that we humans perceive and label. The Standard Model is essentially a taxonomy of particle species: it lists elementary particles (electrons, quarks, neutrinos, photons, etc.) and their interactions via force-carrying particles (like gluons or the Higgs boson). We speak of particles as if they were identifiable, countable entities – the electron, an electron, the Higgs boson – and celebrate discoveries of new particles as if adding new “entries” to nature’s inventory. Yet there is a striking irony here: according to relativistic quantum field theory, particles are not fundamental at all. In QFT, particles are viewed as excited states or quanta of underlying fields. They are useful emergent concepts, not the basic building blocks of reality.

Put bluntly, the consensus among many physicists and philosophers of physics is that QFT “does not describe particles” as fundamental entities. We call it “particle physics,” and indeed in experiments like those at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider we see localized detection events we interpret as particles, but in the quantum field description, what’s really fundamental is the field (or the quantum state of a field) rather than little billiard-ball objects. The particle notion, though central to how we apply the theory, “should be demoted in QFT from fundamental to derivative status”. In fact, one finds that the notion of a particle can be frame-dependent – a famous example is the Unruh effect, in which an accelerating observer perceives a warm bath of particles in the vacuum that an inertial observer sees as empty space. Such phenomena show that “particle” is not a God-given label, but rather a concept that makes sense only relative to a given state or observer. Reality itself, per QFT, is a continuous field (or set of fields) and what we call a particle is more like a localized disturbance or fold in that field.

Quantum field theory thereby blurs the boundary between particles and non-particles. In QFT, you can have states that don’t even have a well-defined number of particles – particle number becomes an approximate or contextual property. For example, a high-energy photon can morph into an electron–positron pair and vice versa; the “number of particles” is not fixed. Indeed, one of the main motivations for introducing QFT was to handle situations where particle number is not conserved. In a simple electron-positron annihilation, two particles disappear and one photon appears; later that photon might produce three particles (say a quark, antiquark, and gluon). We started with two and ended with three – a clear violation of any naive counting rule. Quantum theory accepts creation and annihilation of quanta as a fact of life. From a field perspective, it’s simply energy flowing into different modes of the field, but from a particle perspective, it looks like particles can pop in and out of existence.

This leads to a profound point: what we regard as “elementary particles” might be akin to the crest of a wave on the ocean – a transient, emergent form rather than an indivisible substance. The field (the ocean) is the continuous reality; the particle is a useful fiction, a high-energy blink on our detectors that we interpret as a discrete thing. Quantum fields themselves, however, are spread throughout space, continuous, and in constant fluctuation. As one essay eloquently put it, “everything might be made of granules, but all granules are made of folded-up continuous fields that we simply measure as granular… Discrete particles, in other words, are folds in continuous fields”. In QFT, the vacuum is not empty at all, but a roiling sea of field fluctuations – “an undulating ocean (the Dirac sea) in which all discrete things are its folded-up bubbles”. Our theories label those bubbles as “particles,” but the label might be more reflective of our measurement methods and cognitive biases than of nature’s innermost ontology.

It’s not just particle count that is problematic – even the concept of a well-defined individual particle can get fuzzy. Quantum particles of the same type are perfectly indistinguishable in principle (all electrons are identical, with no “serial numbers”), which already challenges the classical idea of tracking individual objects. In quantum statistics, particles lose their identity and only combinations matter. Furthermore, the very term “particle” conjures an image of a tiny localized object, yet quantum “particles” can behave like spread-out waves. The wave–particle duality taught in textbooks underscores that our language (wave vs. particle) is trying to force quantum entities into classical categories that don’t really fit. As Heisenberg and Bohr realized nearly a century ago, we cannot talk about a quantum system having a definite trajectory like a little planet orbiting – the concept simply breaks down. Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle quantitatively expresses why: precise position and momentum together can’t be ascribed. In fact, “the uncertainty relations preclude continuous trajectories by treating quantum measurements as inherently discrete” – each measurement gives a result at a moment, but you can’t string those into a continuous path without contradiction. Quantum measurements come in discrete, indivisible “clicks,” not as a continuous tracking of reality. We get a dot on a screen, then another dot, building up a pattern. But between those detections, speaking of a well-defined path or even an existence of the particle in a classical sense can lead us astray.

Consider the classic double-slit experiment. If electrons are fired one by one through a pair of slits, they arrive as discrete impacts on a screen – each electron is detected as a single dot, a “particle” event. But as the pattern of many such electrons builds up, an interference pattern emerges, the kind we would expect if waves were passing through both slits and interfering. This experiment has been famously called by Feynman “the one mystery” of quantum mechanics. How can each electron, seemingly a particle, contribute to an interference pattern as if it went through both slits as a wave? If we open both slits, some positions on the screen that were previously illuminated (with one slit) become dark – adding the second path causes some electrons to disappear from certain locations due to destructive interference. It’s as if the electron “knows” both slits are open. The wave–particle paradox here highlights the tension between our boxed concepts (“it’s a particle” versus “no, it’s a wave”). Quantum theory’s formalism sidesteps the paradox by using a wavefunction – a mathematical object that encodes probabilities – but when we observe, we still only see particle clicks. We have one foot in a continuous wave description and one foot in a discrete particle outcome. We get probabilities from the wavefunction and actualities as the detector clicks, and the connection between the two is a matter of interpretation and debate (the infamous measurement problem).

This brings us to another key point: the irreducibly probabilistic nature of quantum predictions. In quantum mechanics (and even more so in quantum field theory), we can never predict a single event with certainty, only the distribution of outcomes if we repeat an experiment many times. Traditional interpretations say this randomness isn’t just due to hidden details we haven’t figured out – it is fundamental. That is deeply unsettling if one believes a physical theory ought to tell us what is happening out there. Instead, quantum theory gives us a recipe to calculate likelihoods. We often hear that this probabilistic approach works perfectly and has been confirmed to astonishing precision. True – but it also might be telling us that our theory is more about our knowledge (or information) of the system than about an omniscient description of reality itself. On the Information Philosopher website, the quantum mystery is framed this way: “how mere ‘probabilities’ can causally control (statistically) the positions of material particles – how immaterial information can affect the material world”. In other words, we have this mathematical wave of probability (something abstract, not made of substance) that nonetheless seems to guide where real electrons end up hitting the screen. It’s as if our theory interposes an algorithm between reality and us, an algorithm that is superb at predicting the aggregate outcomes, yet we’re left scratching our heads about what is really happening to each electron. Is the electron itself a smear of possibility (wave) that “collapses” to a point (particle) when observed? Or is it always a particle guided by a pilot wave (as Bohm’s interpretation suggests)? Or are there many parallel worlds in which each outcome happens? We don’t know – and for our purposes here, the takeaway is that the very concepts of particle, wave, location, trajectory, etc., all start to wobble at quantum scales. We still use those words (particle, wave, etc.) in our theories, but perhaps only because we haven’t conceived a better language for quantum reality.

Cracks in the Foundation: Examples That Defy Our Conceptual Boxes

Let’s dig deeper into a few illustrative examples that expose how our “labeled, boxed definitions” in physics might be at odds with what nature really is:

- Uncertainty in Particle Number (and Identity): In everyday chemistry or classical physics, we assume the number of particles (atoms, molecules) is an invariant – you have 2 atoms of hydrogen and 1 of oxygen before a reaction, and 2 of hydrogen and 1 of oxygen after, just bonded differently, for instance. Not so in quantum physics at high energies: particles can be created or annihilated in accordance with Einstein’s E=mc^2. In high-energy collisions, we routinely see dozens of new particles materialize from kinetic energy. More subtly, even defining what counts as a particle can depend on your state of motion. As mentioned, an accelerating observer sees a “thermal soup” of particles where an inertial observer sees none (the Unruh effect). In quantum field theory on curved spacetime (like near a black hole horizon), the notion of a vacuum and particles becomes even more observer-dependent. This unsettles the very idea that “particle” is a fundamental category of reality – it seems to be an artifact of how we look. Philosophers of physics have concluded that “QFT cannot be given a particle interpretation” in any globally consistent way. Instead, the particle concept has a limited applicability – useful in certain contexts (like an approximately flat spacetime or at low energies where creations/annihilations are rare) – but not a universal, ontologically fundamental feature. So, while our Standard Model comes packaged as if nature were like a zoo of separate particle species, QFT hints that it’s really a single interconnected field reality, with the “animals” in the zoo being more like different excited patterns of one continuum.

- Wave–Particle Duality and Complementarity: As discussed with the double-slit experiment, quantum entities exhibit both particle-like and wave-like behaviors, but never both at the same time. If you set up an experiment to detect particle attributes (which slit did the electron go through?), you lose the interference pattern – it behaves like a particle localized to one path. If you set up the experiment to preserve wave interference, you lose which-path information – the electron cannot be said to have gone through one slit or the other, it’s somehow a delocalized wave until detection. This duality forced physicists like Bohr to adopt the principle of complementarity: you can have a wave description or a particle description, depending on experimental context, but not a single mental picture that contains both. This feels like an indictment of human concepts: “wave” and “particle” are mutually exclusive classical concepts, and a quantum system just isn’t either one in classical terms. When forced into one category by measurement, it behaves accordingly, but that’s more about the measuring apparatus plus system as a whole. The quantum state itself, prior to a choice of observation, doesn’t live in ordinary space like a billiard ball or a water wave – it lives in an abstract Hilbert space of possibilities. We routinely impose discrete labels (photon here, electron there; spin up vs. spin down; this path vs. that path), yet quantum reality, between observations, seems to laugh at such definitive labeling. Perhaps the error is in our insistence that nature must be describable in terms of “either/or” classical categories – maybe a quantum object just is something that cannot be captured by the words particle or wave, those are just crutches we use to discuss aspects of it.

- The Statistical Nature of Prediction: In classical physics, unpredictability usually meant ignorance – if we don’t know exactly how the dice were thrown, we can’t predict the outcome, but in principle if we did know all initial conditions, the outcome is determined. In quantum physics, even with complete knowledge of the wavefunction (the state of the system), only probabilities for outcomes can be obtained. Many physicists have come to accept that as a fact: nature, at a fundamental level, behaves randomly (to the extent that even an omniscient observer could only calculate probabilities). But let’s step back: this is a huge pill to swallow. Another way to view it is that our theory is incomplete in a very particular way – it can get the frequencies of outcomes right, but perhaps not the story of individual outcomes. In other words, it correlates with reality at the level of ensembles, but maybe doesn’t capture what’s going on with each particle. Einstein, famously dissatisfied with quantum indeterminism, quipped that the theory might be right in a statistical sense but still not a complete description of reality (“God does not play dice” being the popular paraphrase). Whether or not one agrees with Einstein’s realism, it’s worth noting that other areas of science have seen similar transitions: for instance, thermodynamics gave us statistical predictions about gases long before we understood the molecular dynamics underneath. In time we realized the randomness in a gas was apparent – arising from ignorance of details – not fundamental randomness of nature. Could it be that the inherent quantum randomness is likewise a sign that we’re using the wrong descriptive language? Perhaps there is some sub-quantum level of description – not in terms of classical trajectories and positions, but in some other novel terms – that would restore a causal story beneath the randomness. As of now, no sub-quantum theory (like hidden variable theories) has been experimentally validated, and indeed quantum experiments strongly constrain any deeper “deterministic” explanation (Bell’s theorem and related tests have ruled out a wide class of local hidden-variable models). However, it’s possible that our conception of “locality” or “causality” might need revision too. The main point here is not to advocate a specific alternative, but to underscore that quantum theory’s reliance on probabilistic outcomes might reflect a limitation of the framework – a kind of veil over reality rather than a window into it.

In all these examples, we see a pattern: our theories work, yet they leave us with conceptual paradoxes or ambiguities whenever we try to interpret what the math is saying in ordinary language. It’s as if nature is a continuous, holistic soup, but we keep carving it into pieces – particles, waves, trajectories, separate forces – to fit it into our cognitive toolkit. We get incredibly good predictions out of this (no one can deny the success of quantum electrodynamics or the Standard Model’s match to experiment), but when we ask, “What is an electron really? What is it doing between observations? What is space-time at the smallest scale?” – our theories fall into either silence or self-contradiction. We may be approximating reality with a patchwork of discrete concepts that don’t hold at a fundamental level.

Path Integrals and the Chaotic Quantum Soup of Reality

In everyday life, we imagine the world as composed of distinct objects following neat trajectories: a photon zips in a straight line, a proton contains three quarks sitting tidily together. But modern physics paints a far messier—and more fascinating—picture. At the deepest level, reality behaves less like a sequence of clean events and more like a statistical average over all possibilities, a kind of emergent order precipitating out of chaos. In this expanded exploration, we’ll see how Richard Feynman’s path integral formulation exemplifies this view, treating a particle’s behavior as a sum over histories rather than one definite path. We’ll look at how a photon in quantum electrodynamics (QED) is not modeled as a single bullet tracing a line, but as an amalgam of countless potential paths—paths that can split, merge, and even loop backward in time. We’ll then turn to protons and neutrons, which textbooks depict as three-quark bound states, and discover that in reality they are a frothing brew of gluons and virtual quark-antiquark pairs, only on average coalescing into the particles we know. These examples reinforce a central theme: the world is not made of discrete, static pieces, but of probabilistic, fluid processes that only masquerade as solid objects at our human scale. Perhaps our difficulty in unifying physics’ laws stems from the fact that we insist on using sharp-edged mathematical constructs to describe a domain that is fundamentally continuous, borderless, and in flux.

Feynman’s Sum Over Histories: All Paths, All Possibilities

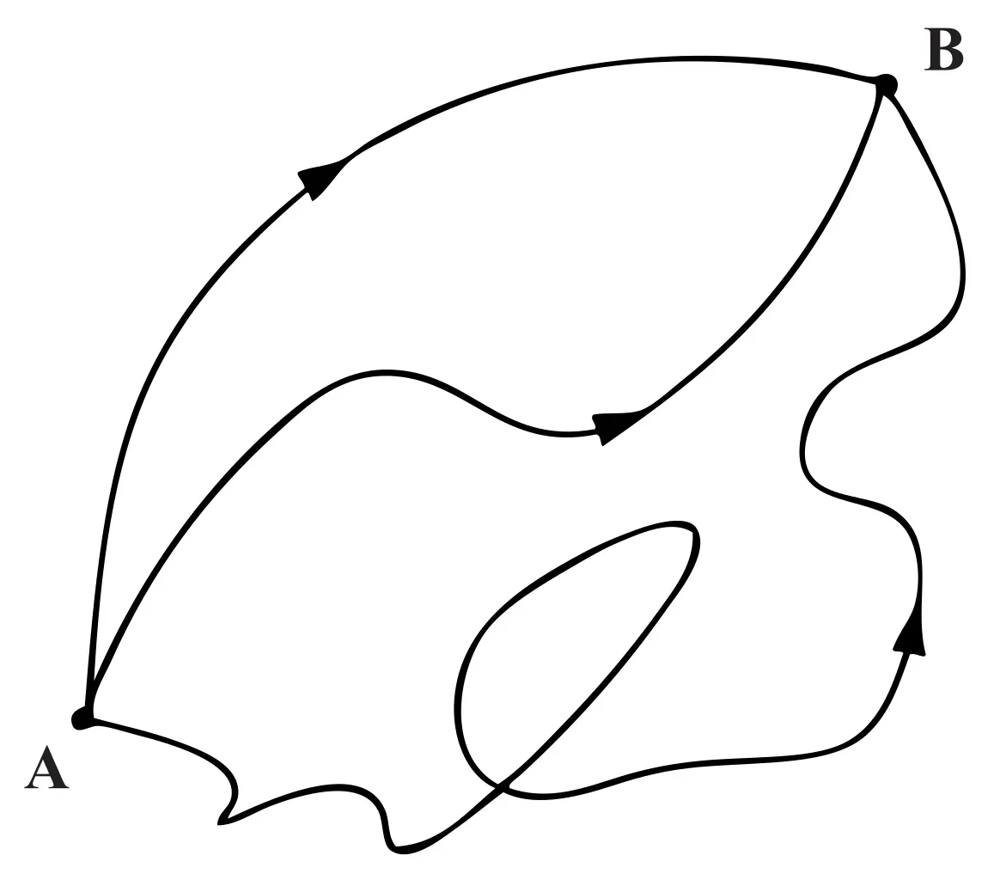

Classically, if you throw a ball or shine a flashlight, physics tells you there’s one path the object will take, determined by initial conditions and forces. Quantum theory radically departs from this intuition. Richard Feynman’s path integral formulation (also known as the “sum over histories”) tells us that to predict what a particle will do, we must consider every conceivable path from start to finish, not just the single path of least action. For example, to calculate the probability of a particle traveling from point A to point B, Feynman’s recipe says to imagine the particle taking every possible route in spacetime – not only the straight-line trajectory we’d expect classically, but wild detours, loops, and meanderings of all kinds(einstein-online.info). Each such path is assigned a quantum amplitude (a complex number) based on its action, and the sum of all these amplitudes determines the particle’s overall behavior.

Figure: In the path integral picture, a particle traveling from A to B must be imagined as simultaneously taking every possible route through space. Each squiggly line here is a cartoon of one possible path; in reality there are infinitely many. In quantum mechanics, the contributions of all paths are summed (with appropriate phases) to compute the probability of the particle’s arrival(einstein-online.info). Paths that would be classically absurd—wandering off to the Andromeda galaxy and back—are included too, though their contributions typically cancel out or suppress each other through interference.

This sum over all paths is not just a metaphor; it’s a precise calculational tool that has yielded astonishingly accurate results. In practice, many of the extremely contorted paths cancel out due to interference: paths with certain phases subtract from others, washing out much of the craziness. Meanwhile, paths near the classical trajectory (the shortest, least action route) tend to reinforce each other and dominate the sum(medium.com). The upshot is that, for large-scale events, a quantum particle appears to have followed a single reasonable path, since all the bizarre alternatives more or less canceled themselves into silence. This is why, despite the quantum weirdness underneath, a beam of light still travels in a straight line in practice and a baseball follows a parabola. But that straight line or parabola is really an emergent average—a tidy outline drawn by summing over zillions of underlying possibilities.

Crucially, nothing in the path integral formalism says the particle only exists along one path and not the others. All the paths are considered, even those that seem impossible. Physicist Markus Pössel illustrates this well: “It neglects to show the cases in which the particle visits New York, Ulan Bator, or even the moon or the Andromeda Galaxy before arriving at its destination… take into account all ways of travelling from A to B, however outlandish they may seem.”(einstein-online.info) In Feynman’s formulation, reality at the micro-scale is a vast superposition of histories. What we observe as a single outcome is the result of this grand interference pattern where most histories cancel out and only a few reinforce.

The Chaotic Trajectory of a Photon in QED

Nowhere is this idea more vividly realized than in quantum electrodynamics (QED), the quantum theory of light and electrons. In QED, a photon—a particle of light—traveling from a source to a detector is not envisioned as a little billiard ball flying along one straight line. Instead, the photon’s behavior is obtained by summing over all possible ways that journey could pan out. Some of those ways are straightforward (the photon goes directly to the detector), while others are fantastical: the photon might loop around, take a long zigzag path, or even briefly split into other particles along the way. According to Feynman, a photon “doesn’t follow just one route. Instead, it takes every possible route simultaneously”(medium.com). If you could “see” the quantum reality, you’d picture the photon exploring all paths – a haze of probabilistic routes through space – and interfering with itself en route to its destination.

What does this mean physically? It means that processes we wouldn’t allow in classical physics do contribute to how light behaves. In QED, anything that is not forbidden will happen (in the sense of contributing to the amplitude). For instance, a photon can spontaneously transform into an electron–positron pair and then recombine back into a photon – as long as it happens within a short enough interval to satisfy quantum uncertainty. In fact, the QED equations explicitly allow this: a photon temporarily splitting into a positron and electron) and the inverse are fundamental interactions(physics.stackexchange.com). This means that even when a photon is just “traveling” through empty space, there is a possibility (a virtual process) where it blinks into an electron-positron pair and back. Such a pair is virtual – it pops in and out of existence too quickly to be directly observed – but it contributes to the photon’s overall propagation. In a Feynman diagram, we would picture this as the photon line diverging into an electron line and a positron line, which later merge back into a single photon line. During that ephemeral split-second, the “photon” wasn’t a photon at all, but a particle–antiparticle pair. This is not science fiction; it’s part of how QED explains phenomena like vacuum polarization, where a photon traveling through the vacuum is influenced by the possibility of these virtual particle pairs.

Moreover, QED’s mathematics permits strange time-reversed sequences as well. Richard Feynman famously pointed out that an antiparticle can be viewed as a particle traveling backward in time. In our photon example, the positron in the virtual pair can be interpreted as an electron moving backward in time through the intermediate stage(bigthink.com). This interpretation, while mind-bending, elegantly makes sense of certain symmetries in particle interactions. So among the photon’s many possible “histories” are ones where an electron zigzags into the past (as a positron) before rejoining its partner to emit a photon again. In effect, the photon’s propagation amplitude includes contributions from processes that look like the photon splitting, merging, and looping in time.

We should emphasize that these exotic-sounding histories are not literally alternate realities we could pick apart; rather, they are components of a calculation – the terms in an infinite series that defines the photon’s behavior. We never see a photon “pause and turn into matter” in mid-flight in a detector; what we see is just the final accumulated effect. At our macroscopic scale of observation, all of this quantum chaos manifests simply as “a photon arrived at the detector.” The messy intermediate possibilities are hidden from direct view, because they mostly cancel or are too fleeting to leave a distinct mark. What our eyes and instruments register as a single particle is really the averaged-out result of uncountably many simultaneous quantum processes. As one physicist put it, QFT (quantum field theory) doesn’t give you a single picture of a photon propagating; “all QFT gives you is the probability amplitude to go from A to B… corrected by some suggestive pictures which show the photon splitting and recombining”(physics.stackexchange.com). In other words, a photon’s identity is a collective haze of paths and virtual interactions, which only coalesces into a familiar particle-like event when we observe it.

It’s instructive to consider a simple analogy: imagine shining a beam of light and asking how it travels. Classically, we’d draw a straight arrow. In the quantum view, we must imagine a swarm of arrows – one for every path through space and time – each arrow waving and rotating (due to phase). Most of these arrows point every which way and cancel out with neighbors. But the arrows nearest the straight-line path all point roughly in the same direction and add up. Thus the net effect is an arrow along the straight line – the observed photon path – even though underneath, a zillion squiggly routes were taken. As Feynman described in his lectures, when light reflects off a mirror, one must consider every possible point it could reflect (even ones far off to the sides); in the end, the contributions from most points cancel, and only those near the path of equal angles reinforce, which is why the law of reflection holds on average. Similarly, for a photon traveling through space, the dominant contribution comes from near-classical paths while extremely baroque excursions are self-cancelling(medium.com)(medium.com). Our macroscale reality thus fools us into thinking the photon “just went straight,” whereas in truth it was constantly jittering through all possibilities allowed by physics.

The take-home message is that the “photon” we observe is an emergent phenomenon. It’s what the underlying quantum soup averages out to look like. At human scales or even atomic scales, the sum-over-histories produces stable patterns—like the familiar particle flying from A to B. But if we peer into the quantum underpinnings, that stability dissolves into a vast superposition of ghost paths and virtual particles. Reality, at its core, is less like a bullet train and more like a haze of probabilistic happenings that only collectively behave like a train.

Protons and Neutrons: Frothing Quark-Gluon Seas

If the photon is stranger than we naively think, protons and neutrons (the constituents of atomic nuclei) are perhaps stranger still. The simplistic picture taught in school is that a proton is a bound state of three quarks (two up quarks and one down quark) held together by gluons, and a neutron is three quarks (two down, one up). This three-quark model isn’t wrong – but it’s woefully incomplete. In reality, those three valence quarks are just the tip of an enormous iceberg of quantum fields. A proton is not three tiny balls stuck together; it is a seething bag of quarks, antiquarks, and gluons in constant flux.

One dramatic indication of this comes from the proton’s mass. The rest mass of a proton is about 938 MeV (mega-electronvolts) in energy units. If you add up the masses of two up quarks and one down quark (the three quarks inside), you get only around 1% of that total mass. In other words, 99% of a proton’s mass is coming from something other than the quarks’ masses. Those three quarks are featherweights, yet the proton is heavy. As physicist Krishna Rajagopal explains, “the proton is often described as made of two up quarks and one down quark… But a proton weighs about fifty times as much as these three quarks! Thus a proton (or neutron, or any hadron) must be a very complicated bound state of many quarks, antiquarks, and gluons”(physics.mit.edu). In fact, calculations show that more than 90% of the proton’s mass arises entirely from the dynamics of quarks and gluons whizzing around inside(physics.aps.org). The quarks’ kinetic energy, the energy of the gluon fields, and the effects of quantum fluctuations generate the bulk of the mass, not the quarks’ rest-mass itself.

What are all these extra “constituents” filling the proton? Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD), the theory of quarks and gluons, tells us that the vacuum itself is active and thick with fluctuating fields. Inside a proton, the strong force (carried by gluons) is so intense that gluons are being radiated and absorbed constantly, and quark-antiquark pairs are continuously being pulled out of the vacuum and disappearing again. At any given moment, along with the three valence quarks, a proton contains a cloud of gluons (literally hundreds of them, carrying the binding force) and a sea of transient quark pairs of various flavors popping in and out. These are often called sea quarks or virtual quarks. The proton’s three “real” quarks are really just an excess of three quarks over antiquarks in that sea – a net count that gives the proton its identity (for example, its +1 electric charge). But the actual content is far more crowded and chaotic.

A proton or neutron is thus “composed of a dense, frothing mess of other particles: quarks…and gluons”(physics.aps.org). This quote from an APS Physics article captures it perfectly – a dense, frothing mess. The quarks and gluons are in constant motion, and their interactions are extremely energetic. The strong force’s field is always jittering with fluctuations. In the QCD vacuum (the environment in which quarks and gluons exist), “the vacuum is a frothing, seething sea of quarks, anti-quarks, and gluons”(physics.mit.edu) rather than an empty void. The proton is really a little drop of this sea, kept together by the strong force’s confining effect.

What we call a “proton” is in some sense an emergent, relatively stable pattern within this sea of quantum activity. It’s a bit like a stable whirlpool in a turbulent lake: water is flowing in and out of the whirlpool, but the pattern of the whirlpool persists over time. Similarly, quarks and gluons rush around, get exchanged, and even convert into each other (a gluon can split into a quark-antiquark pair, then those can annihilate back into a gluon, etc.), but an overall stable three-quark-bound-state pattern endures, which we name the proton. If you try to isolate a single quark from the proton, you can’t – pulling a quark out just leads to more quark-antiquark pairs forming (due to the strong force’s property of confinement). So the proton is permanently “dressy,” surrounded by a cloak of extra particles.

To get a sense of scale: if you peer inside a proton, you won’t find three quark marbles sitting quietly. You’ll find something more akin to a quantum storm. At any instant, there are many quark-antiquark pairs present (predominantly up and down quarks, but also some heavier flavors popping up briefly) and a teeming swarm of gluons flitting about like fireflies. These gluons carry momentum and energy; in fact, roughly speaking, the gluons carry about half the proton’s momentum on average, the sea quarks carry a significant chunk, and the valence quarks carry the rest. The stability of the proton comes from a delicate balance: the quark triplet is bound by a sea of gluons, and that interaction energy is mass-energy that gives the proton heft (thanks to E=mc^2). In lattice QCD simulations and high-energy scattering experiments, this picture is confirmed: a proton is a hyper-dynamic object, a frothing quark-gluon soup bound into a roughly spherical blob.

The neutron is the same way (with a different quark composition net total). It’s not three static quarks and nothing else; it’s three valence quarks plus a shifting mess of gluons and quark pairs. Even mesons (particles made of one quark and one antiquark, like pions) are not just that pair in isolation – they too are embedded in the sea of the QCD vacuum and have additional fluctuations. The concept of a “particle” in quantum field theory is a bit like a stable resonance or a persistent fluctuation in an underlying field. For nucleons, the fields in question are the quark and gluon fields of QCD.

So, while a chemistry or physics textbook might depict a proton as three colored spheres (to represent quarks) stuck together by springs (to represent gluon bonds), the truth is far more complex and wiggly. A more accurate depiction would be a bubble full of activity: writhing tubes of color force fields, quark dots blinking in and out, gluon tendrils stretching and contracting. It is only when you average over time (or probe the proton at not-too-high resolution) that it appears as a unified object with definite properties like charge, mass, and spin. Those properties emerge from the collective behavior of all the constituents and their interactions. In a very real sense, the proton itself is an emergent regularity of an underlying quantum storm. There isn’t a hard, permanent boundary that says “this part is the proton, and outside is not” – rather, the proton is defined by a clustering of energy and quantum numbers that is relatively stable and localizable.

The phrase “frothing mess” is not just colorful language; it reflects that protons and neutrons are fundamentally wave-like and field-like, full of fluctuations, not discrete dot-like particles. The words we use (proton, neutron, photon, electron) are names for simplified, coarse-grained phenomena that arise from a much finer-grained, fluid reality.

Emergent Regularities vs. Fundamental Fluidity

These examples from QED and QCD illustrate a profound point: what we experience as solid, separate objects are in truth emergent patterns floating atop a sea of quantum processes. The world, at bottom, is not made of tiny billiard balls or Lego blocks; it’s made of interacting fields and probabilities that congeal into particle-like behaviors only when observed in aggregate. As physicist Carlo Rovelli eloquently writes, “We slice up the reality surrounding us into objects. But reality is not made up of discrete objects. It is a variable flux.”(cpcglobal.org) Consider a wave in the ocean: we give it a name, we track its crest from here to there, but it has no distinct edge independent of the water around it – it’s a dynamic form, not a separate thing. The same is true of a mountain, Rovelli notes: where does one mountain end and the next begin? Any boundary we assign is somewhat arbitrary(cpcglobal.org). Likewise, the boundaries of what we call a “particle” or an “object” in physics are fuzzy and conventional. They are useful ideas for bookkeeping, but nature itself isn’t obliged to respect those neat borders.

Reality, when examined closely, seems continuous and borderless in this way. The divisions we make – photons here, electrons there; quarks here, gluons there; even space vs. matter – are often convenient fictions or approximations. The success of quantum field theory suggests that everything is fields, and particles are just localized excitations of those fields. Fields by definition are smeared-out and overlapping. An electron, for example, is an excitation of an electron field that extends throughout space. It’s only mostly concentrated in one place. And a proton is an excitation of the quark and gluon fields, which are pervasive and interacting. When we insist on picturing these as tiny self-contained balls, we’re forcing a discrete viewpoint onto a fundamentally continuous substrate.

This realization could shed light on why it’s so hard to unify our physical theories or to find a single framework that describes gravity and quantum mechanics together. Our current theories – general relativity on one hand, quantum field theory on the other – are built on certain idealizations. General relativity treats spacetime as a smooth continuum, something we can bend and curve but which has a well-defined geometry. Quantum field theory, while it deals with continuous fields, introduces the notion of discrete quanta and relies on perturbative calculations that handle interactions in piecemeal fashion (virtual particles, Feynman diagrams, etc.). Each theory carves up reality in a different way (for instance, separating matter and spacetime, or treating forces as exchanges of virtual particles). A true theory of everything might require us to let go of some of these carvings and recognize a more holistic picture in which what we call “space,” “time,” “matter,” and “energy” are not fundamental categories, but emergent aspects of a deeper, more fluid reality.

It could be that our mathematical tools and languages, which are inherently symbolic and analytical, struggle to describe a world that doesn’t have clear lines. Mathematics excels at handling well-defined entities and boundaries; even fields are described by equations that assume a kind of continuity and differentiability that might break down at the Planck scale. If nature is, at its core, an unbroken wholeness (to borrow a phrase from physicist David Bohm) or a process rather than a set of things, then our usual way of theorizing – dividing the world into parts and writing equations for the parts – may be inadequate or need radical revision.

The unification problem in physics may thus be related to an epistemological problem: we are trying to find a single set of symbols (a single language of mathematics) to describe something that might not be easily symbolized in discrete chunks. We’re looking for the joints in a statue that is actually carved from a single stone. As a result, every time we think we have a handle on one aspect (say, quantum particles), another aspect (smooth spacetime geometry, or the information content of black holes, etc.) defies incorporation, because the very concepts of “particle” or “spacetime point” might be emergent and approximate.

In simpler terms, our struggle to unify physics may stem from trying to force a fluid reality into rigid theoretical boxes. We invent separate formalisms for waves and particles, for fields and geometry, for quantum discreteness and continuum spacetime. But perhaps these dichotomies are of our own making. The universe itself might not recognize the border between matter and space – it could be all one thing in different guises. Our minds like to label one part “photon,” another part “vacuum,” one part “quark,” another part “gluon,” but in truth those labels attach to transient, overlapping excitations of an underlying field system that is all-encompassing.

As Rovelli reminds us, asking exactly where one entity ends and another begins can be a misguided question(cpcglobal.org). The more pertinent reality might be the network of interactions and relations among what we call objects(cpcglobal.org). In quantum physics, this is evident: particles are defined by how they interact (an electron is what electrons do, exchanging photons with other charges, etc.). Even space and time might be emergent from relations (as some quantum gravity approaches like loop quantum gravity or holographic theories suggest). So to truly unify physics, we may need to embrace the idea that at the fundamental level, there are no separate pieces to unify – there is just one vast, interconnected process.

In summary, modern physics urges us to let go of the 19th-century clockwork image of reality. Instead of a universe made of billiard-ball particles following precise orbits, we have a universe of quantum fields, where every “event” is a blend of countless possibilities and every “object” is a stable pattern in an ongoing flux. The solidity and discreteness we perceive are like the calm surface of a boiling sea – deceptive markers of order that hide the roiling chaos underneath. Recognizing this grants us a deeper humility about our models. The equations of physics don’t carve nature at its joints; they approximate nature by imposing joints. The quest ahead is to refine our concepts so that we stop mistaking the maps (our symbols and categories) for the territory (the physical world). The territory, as far as we can tell now, is an ever-changing, probabilistic, and holistic soup. Out of that soup emerge the photons that light our world and the protons that build our bodies – emergent regularities that our coarse senses interpret as solid reality. But when we peer with a quantum eye, we see that reality’s foundation is fluid: a rich superposition of paths, a frothing sea of fluctuations, a world where certainty dissolves into a spectrum of possibilities, all of which together create the illusion of the stable, familiar world we experience. And in that realization lies perhaps the first step to truly reconciling the theories of physics – by understanding that, at base, everything flows.

Are Our Conceptual Tools the Real Culprit?

It’s a natural response to think that the problems described above will be solved with more data, higher energies, or a new breakthrough that finds the “right theory” – a final equation that unifies physics. But what if the stumbling block is not missing data but a missing perspective? Perhaps we are asking nature questions in a language nature doesn’t speak. We have, by default, used mathematics as the language of physics – and it’s an incredibly powerful language. But mathematics itself is a human construct, built on logic and often on discrete symbols and operations. Even continuum mathematics (calculus, real analysis) reduces things to limits of discrete operations, summing tiny pieces. Could it be that by forcing nature into a mathematical framework, we are inevitably coarse-graining reality into countable or separable components, because that’s what our minds (and thus our math) excel at?

The question sounds almost heretical: after all, how could physics proceed without mathematics? Surely we’re not proposing to abandon math. Rather, the provocation is that we might need to re-examine the foundational assumptions and primitives in our mathematical physics framework. We treat certain abstractions – point particles, spacetime points, wavefunctions in Hilbert space, quantum fields at each point in spacetime – as if they were the “real stuff” of the world. But maybe they are akin to the coordinates on a map. As the philosopher Alfred Korzybski famously said, “the map is not the territory”. Our equations and models are maps: they have a similar structure to reality and that’s why they’re useful, but we should not confuse them with reality itself. In statistics, there’s an aphorism: “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” The idea is that any finite model is a simplification of the world and leaves something out – yet if it captures enough salient structure, it can make good predictions. Physics models are no exception. Newton’s gravitational model was “wrong” (not the full truth) but very useful. Even General Relativity, for all its triumphs, is probably not the final story (it breaks down at singularities, for example). Quantum field theory might be seen not as literal truth but as an extremely useful fiction or instrument – something that lets us calculate observable outcomes without necessarily revealing the underlying cause for those outcomes.

In philosophy of science, this stance is known as instrumentalism or constructive empiricism. The physicist Niels Bohr was often accused of this – caring only about predictive outcomes (“outward phenomena”) and dismissing questions about underlying reality as metaphysical distraction. Bas van Fraassen, a contemporary philosopher, explicitly argues that science aims not at truth per se but at “empirically adequate” theories, meaning theories that correctly predict observable phenomena. Such a theory need not be true in a literal, ontological sense – it just needs to save the appearances. As one summary put it: “A true theory will be empirically adequate, but an empirically adequate theory need not be true.”. This is a perfectly defensible view: it might be that what quantum mechanics gives us is an empirically adequate story (actually, an algorithm) for predicting experiments, without telling us what things like electrons are when we’re not looking. We have to consider the possibility that our entire conceptual framework in physics is a kind of “correlative mythology” – a set of stories and equations that correlate with nature’s behavior (especially the parts we can measure), but do not necessarily capture nature’s essence. By “mythology” here, we don’t mean falsehood, but rather a foundational narrative or model that a culture (in this case, the scientific community) lives by. It is “highly functional”, in that it allows us to manipulate and predict aspects of the world, but it might not reflect the underlying ontology – the actual entities and their mode of existence.

To sharpen this point, consider how forces and fields are described. We often speak of the “force of gravity” or “electromagnetic field” as if they were tangible things or substances filling space. In the field view, we replaced the older notion of force-at-a-distance with fields existing everywhere, assigning a quantity to every point in space and time. But is the field real, or is it a mathematical convenience? Michael Faraday, who introduced field lines, conceived of them as physically real. Later, fields became the central reality in physics with Maxwell’s equations. Yet then along came quantum mechanics, and fields were quantized into particles, swinging the pendulum back towards discrete points (field quanta). Now, in quantum field theory, we have this hybrid view – fields that can produce particles. Which is the reality? We don’t know. Perhaps neither is quite right. Perhaps “field” and “particle” are like the blind men’s descriptions of the elephant; reality might be something that bears only partial resemblance to either classical notion.

David Bohm, a physicist who thought deeply about these questions, proposed the concept of an implicate order – an underlying wholeness in which what we see (the explicate order of particles and objects) is like a projection or unfolded version of a deeper reality. In Bohm’s view, what we consider particles are secondary, “derivative” phenomena: “Bohm suggests that instead of thinking of particles as the fundamental reality, the focus should be on discrete particle-like quanta in a continuous field” – essentially that the continuous field (and beyond that, the implicate order which is even more holistic) is primary, and the particles are just what happens when that deeper order expresses itself in a certain limited way. He described the implicate order as a holomovement – an unbroken, dynamic whole. One commentator summarized Bohm’s idea thus: “the flux of the holomovement, with its implicate order, is the primary reality, while the explicate order of relatively constant material forms is secondary”. In plainer terms, the underlying reality might be an ongoing flux (a soup, if you will), and what we call particles, waves, chairs, stars – all the “things” – are like ripples, patterns, or temporary stabilities within that flux.

If Bohm’s view sounds mystical, note that quantum field theory itself, in standard form, is already telling us something similar: the field is always there, even in vacuum, and particles are just vibrational modes of the field. The Aeon essay we cited earlier echoes this: “quantum fields are nothing but matter in constant motion… an undulating ocean… Discrete particles, in other words, are folds in continuous fields.”. The most mind-bending conclusion that essay draws is that nature is “an enfolded continuum.” It says: “Space-time is not continuous because it is made of quantum granules, but quantum granules are not discrete because they are folds of infinitely continuous vibrating fields. Nature is thus not simply continuous, but an enfolded continuum.”. This paradoxical resolution suggests that the very dichotomy of continuous vs. discrete is a false one – reality might manifest discrete appearances, but those come from an underlying continuum; yet that continuum itself, viewed at another scale, shows discrete quantum jumps, etc. It’s an entwined, layered concept that defies an easy picture. But it hints that our human tendency to classify something as either a or b (wave or particle, continuous or discrete, field or matter) might be inadequate. Reality could transcend these dualistic categories.

The Map Is Not the Territory: When Math Meets Myth

Why do we cling to these categories? The simple answer: because they work – up to a point. Carving the world into pieces and laws has allowed us to predict and control many phenomena. Our mathematical frameworks, though full of human-chosen definitions (like coordinate systems, basis functions, Fock spaces of particle states, etc.), yield correct numbers when we compare to experiments. This success can lull us into thinking the model is the reality. It’s worth remembering that physics does not directly reveal the nature of things; it links measurements to calculations. As long as those calculations come out right, we tend not to question too deeply what the symbols really mean. But as we probe into realms where our models struggle (unification, quantum foundations, etc.), it becomes crucial to reflect on how much of our theory is “merely” a representation.

There is a parallel in the philosophy of mathematics: are mathematical entities like numbers and sets real (Platonism), or are they human inventions that just happen to be useful? Physicists largely act as if math is just a tool – yet when an equation is successful, they start to suspect it’s because nature “obeys” that equation. For example, Paul Dirac famously followed mathematical beauty to predict the positron before it was observed. Eugene Wigner wrote about the “unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics” in describing the physical world. It sometimes feels as if math is a divine language that the cosmos is written in. But there’s another possibility: we evolved to see patterns and do math in a way that is naturally tuned to the patterns of our environment. We shouldn’t be surprised that a species of tool-users and pattern-seekers eventually devised a formal system that captures patterns efficiently – that’s what math is. The fact that math can describe physics is less mysterious if we think of it as the codification of patterns of experience. Of course it will match experience – it was crafted to.

From that perspective, math and physics equations are maps we have drawn that coincide with the territory where we’ve been. However, just as a map can have the correct roads but still omit features like the terrain elevation or the flora, our physical theories might capture certain aspects of reality while omitting or approximating others. They might, for instance, impose discreteness or linearity or symmetry because those are tractable to calculation and reflect what we’ve observed so far, but nature could have additional facets that don’t fit those human-friendly properties. If and when we encounter phenomena that our current frameworks can’t map, it could be like explorers finding a landscape not on any of their charts – they may need a new kind of map.

One historical analogy is the concept of species in biology. For a long time biology was about classifying organisms into species, genera, etc. It felt very concrete – each species was a distinct “kind” of thing. But as evolutionary theory developed, especially in the 20th century, biologists realized that species are not absolute, fixed categories; they are labels we assign along what is actually a continuum of variation and change. There are ring species where the boundary of what is one species or two is fuzzy. There is horizontal gene transfer in microbes blurring species lines. Even among familiar animals, the concept of species can be tricky (think of dogs – all one species but with immense differences, or animals that can hybridize). Darwin himself wrote that he considered the term species as “an arbitrary convenience” for scientists, not a fundamental demarcation in nature. “Species are somewhat arbitrary classifications made for human convenience,” Darwin acknowledged. This doesn’t mean cats and dogs aren’t real, but it means the line we draw between one species and another is part of a human framework to simplify a complex reality of gene pools and reproductive continuums. Nature did not label where one species ends and another begins – we did.

Now consider physics: we label “electron,” “muon,” “photon,” as if they are distinct species of particles. Indeed, they are in our experiments – you can tell them apart by their properties. But could it be that at a deeper level these, too, are emergent categories? For instance, string theory (for all its issues) offers a vision where every particle is just a different vibration mode of the same fundamental string. That’s one way to unify the “species” of particles into a single underlying entity. Even if string theory isn’t correct, the lesson it teaches conceptually is that what we thought were fundamental distinctions might turn out to be unified when seen in a new light. In an underlying “soup” of reality, an electron vs. a quark might be like two patterns or solutions of the same equations, much as a tornado and a whirlpool are two flow patterns in one underlying fluid. We identify them as different phenomena, but they are both fluid dynamics in air or water. Likewise, maybe an electron is a localized knotted twist in some field, whereas a photon is a traveling ripple in that field – different appearances, one continuum underneath.

If this is the case, then our failure to find a “Grand Unified Theory” (let alone a Theory of Everything) might stem from the possibility that we’re formulating the problem in terms of the wrong entities. We keep trying to unify forces and particles – but perhaps at a deeper level there are no distinct forces or particles to unify! It could be that what we call different forces (gravity vs electromagnetism vs nuclear forces) are also emergent distinctions that arise only in a certain regime (e.g., low-energy approximations or particular phases of the universe). Some researchers speculate that space and time themselves might not be fundamental; they could emerge from something more primitive (such as networks of quantum information or relations). If so, asking for a unification within space and time of all forces might be like trying to solve a puzzle that’s set up incorrectly. The pieces won’t fit because the picture we are trying to assemble isn’t the true picture.

In short, perhaps we have been “boxing” reality into fragments (particles, forces, space vs. time, etc.) that don’t correspond to how reality is actually structured. Our cognitive bias is to break problems down into pieces – it’s how science has progressed, via reductionism. Reductionism says: if you understand the smallest pieces and how they interact, you’ll understand everything. This works brilliantly in many cases (molecules -> chemistry -> biology, etc.). But if at the foundational level there are no pieces, or if pieces are simply a convenient fiction, then reductionism hits a wall. There might be only holistic processes or indivisible systems, and trying to reduce them to labeled parts loses something essential.

When the Map Fails: Rethinking the Quest for a Final Theory

The dream of a Grand Unified Theory or Theory of Everything is to have one elegant framework that maps all of physical reality. It assumes that reality has an underlying simplicity that our equations can capture. What we’ve been discussing is the possibility that the true unification required is not just combining the equations of quantum fields and spacetime, but a conceptual revolution in how we describe nature. The “Theory of Everything” might not look like an equation on a T-shirt. It might be a radically new paradigm – one that could even render the term “particle” or “force” obsolete, much as modern biology rendered the idea of fixed species obsolete.

Could it be, for instance, that instead of particles and spacetime, the fundamental description involves something like relationships or information or computations that only in approximation manifest as geometry and particles? There are directions in theoretical physics exploring exactly this: quantum information theory suggests spacetime geometry could emerge from entanglement patterns; some approaches to quantum gravity like the holographic principle imply that the world is better described in terms of two-dimensional information on a boundary than as 3D objects inside. These are speculative, but they share a theme of dissolving the familiar categories.

Another avenue is to consider that maybe mind itself (the way we structure knowledge) imposes limitations. We are accustomed to thinking that any phenomenon must have a mathematical description that is logically consistent and complete. Gödel’s incompleteness theorems in mathematics showed that any sufficiently rich formal system cannot be both complete and consistent – there will be true statements it cannot prove. Perhaps there is a parallel in physics: any finite formulation we invent will leave something about reality unaccounted for. We might unify gravity and quantum mechanics in a set of equations, only to find that those equations raise new questions about reality’s nature that require an even broader framework, ad infinitum. If so, chasing a “final theory” could be like chasing the end of a rainbow – always a bit farther as you approach. This isn’t a reason to despair but rather to be humble: our understanding will likely continue to deepen and change, but with it, our language of physics will also evolve.

What might a future conceptual framework look like? It’s hard to imagine what we don’t yet have language for. But we can take inspiration from some analogies and past shifts:

- When quantum mechanics arrived, it didn’t just tweak Newton’s equations; it introduced non-commuting observables, complex probability amplitudes, and the notion that the observer cannot be separated from the observed in defining phenomena. These were radical conceptual moves that broke with previous boxes (like the idea of a deterministic trajectory or the strict object–observer separation). The result was not a single equation but an entirely new formalism and way of thinking (matrix mechanics, wave mechanics, etc., later unified in Hilbert space formulation). It expanded the conceptual toolbox.

- A future framework might involve an even greater departure. For example, some thinkers like Carlo Rovelli (loop quantum gravity pioneer) have entertained the idea that time and space are not fundamental; instead, relationships or interactions are. If time is emergent, then our whole notion of dynamics (“laws that evolve in time”) would need reformulation. Similarly, if particles are emergent, the notion of “an object with properties” might give way to something like “an event or process”.

- It might be that categories of existence (like what is a “thing”) will be replaced by fluxes or processes. The philosopher Alfred North Whitehead long ago suggested a process-oriented metaphysics – reality as made of events rather than substances. Modern physics is perhaps inching that way: a particle is not a static thing but an excitation event, a transfer of a quantum between field states.

- We may also have to relinquish the comfort of visualizability. Already quantum physics deals in a high-dimensional abstract space. A deeper theory might not map to any simple visual model at all. We might have to interpret its concepts via analogy or via their relationship to observations, without a mental picture. This is how it is, to an extent, with quantum fields – nobody can really imagine a multidimensional field fluctuating in an abstract space, but we can work with the equations and understand the basic ideas.

The take-home message is a shift in attitude: rather than view our current mathematical-conceptual framework as inching closer to an ultimate Truth, we might view it as a particularly successful stage in an ongoing evolution of understanding. It has given us tremendous mileage, but its very success might blind us to its limitations. We must be willing to occasionally step back and question the foundational assumptions and concepts: Are we sure spacetime is a set continuum? Are we sure causality is fundamental and not emergent? Are “one vs many” (the countability of objects) and distinct identity (this particle vs that particle) actually applicable notions at all levels?

When our best efforts to ask a question (like “How do we unify quantum mechanics and gravity?”) run into paradoxes or infinite calculations or unphysical results, it could be a sign that we’re formulating the question in a faulty way. It’s not unlike how asking “Where exactly does a species A become species B on the evolutionary tree?” might be the wrong question – because nature didn’t intend a clear line; it’s a gradual divergence. Likewise, asking “How do these distinctly defined forces unify?” might be wrong if the “forces” were never fundamental to begin with.

Embracing a New Paradigm (Without Losing the Old Maps)

None of this is to dismiss the incredible achievements of physics. The Standard Model and General Relativity are, within their domains, astonishingly accurate maps of reality’s behavior. But what we are contemplating is that these maps might be like maps of different islands, and as we try to chart the ocean between (the domain where quantum gravity matters), our maps don’t join up – perhaps because we need a globe, not flat maps, to cover it all. We need a new representation that can show how the island of quantum physics and the island of relativity connect as part of one planet. Creating that will likely require discarding some cherished flat-map assumptions.

It’s a philosophically humbling stance: our knowledge, for all its power, could be fundamentally limited by the concepts we use. However, it’s also an exciting call to action. It invites interdisciplinary thinking – perhaps insights from philosophy of mind, information theory, or even biology and complex systems could help formulate new metaphors and mathematics for physics. For instance, some have drawn analogies between quantum entanglement in physics and the entangled processes in complex systems or even consciousness, hinting that our ingrained Cartesian cut between subject and object, or this and that, might be transcended in the next theory. These analogies are speculative and must be approached carefully (we must avoid mere hand-waving). But they serve to remind us that sometimes the breakthrough is conceptual rather than technical.

In conclusion, it may turn out that a Grand Unified Theory requires a grand unification of viewpoints: seeing that the discrete “building blocks” and continuous “fields” are dual aspects of something deeper, and that our human need to categorize and count falls short of that “something.” Our mathematical formalism, far from being the ultimate revelation of reality, might then be appreciated as a remarkably consistent mythology – a set of symbols and rules that capture how things appear to us and how they interact in our experiments, without necessarily exposing the noumenon behind the phenomena. This doesn’t make physics less valuable – if anything, it makes it more profound, because it means there will always be new layers to uncover. Reality may be an infinite onion of emergence, and each layer we peel with our theories yields new surprises and new questions.

As science-literate, curious explorers, we should remain open to the idea that the truth of the world might not be expressible fully in our current equation-laden language. We might need to invent new concepts, perhaps as revolutionary as “time” and “space” were to Newton’s contemporaries, or as quantum superposition was to classical physicists. And in doing so, we’ll look back on our present frameworks not as failures – they are amazingly successful within their scope – but as stepping stones in an ongoing journey. Our current physics theories are like myths that work – they capture patterns of reality and allow control over nature (just as ancient mythologies encoded useful knowledge about seasons or navigation in story form). But no myth captures the whole truth. The map is not the territory. By recognizing the cracks in our conceptual infrastructure, we prepare the ground for the next scientific revolution – one that may finally let us see the “soup” of reality without immediately trying to freeze it into particles and grids.

In summary: The difficulty in uniting relativity and quantum theory, the strange dualities and uncertainties of quantum physics, and the deeply statistical character of our predictions all hint that something in our thinking needs to evolve. Perhaps the question is not “When will we have all the data to complete our theories?” but “Do our present theories ask the right questions in the right way?” It could be that our tendency to discretize and categorize – to put nature in neat labeled boxes – is anathema to understanding a reality that could be holistic, fluid, and unbroken at its core. Embracing that possibility is challenging, but it might be the key to breakthroughs. As we move forward, the most important tool will not be a bigger particle accelerator or a larger telescope (though those help), but a keen philosophical openness – a willingness to question the foundations and, if necessary, redraw the very blueprint of fundamental physics. Only then will we inch closer to a framework that describes reality on its own terms, rather than merely mapping it onto ours.

Sources:

- Rovelli, Carlo. Reality Is Not What It Seems: The Journey to Quantum Gravity. 2016. (Discusses how space and time could be emergent and how discrete “atoms” of space might exist, yet hints at deeper continuity.)

- Feynman, Richard. The Character of Physical Law, Chapter 6. (Feynman’s lectures discussing the double-slit experiment as containing “the only mystery” of quantum mechanics.)

- Musgrave, Alan. “The ‘Miracle Argument’ for Scientific Realism.” The Rutherford Journal. (Summarizes Bas van Fraassen’s view that empirical adequacy is the aim of science, not literal truth.)

- Fraser, Doreen. “Particles in Quantum Field Theory.” Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Physics, 2017. (Explains the consensus that QFT does not include particles as fundamental entities, and why the particle concept is of limited applicability in QFT.)

- Aeon – “Is nature continuous or discrete? How the atomist error was born”. (Makes the case that modern physics inherited an atomistic bias, and that quantum field theory actually suggests an underlying continuum with particles as emergent folds.)

- “Weak Particle Presence” – Foundations of Physics, 2025. (Discusses how quantum measurements being discrete in time challenge the notion of continuous trajectories, and how QFT blurs the line between particles and fields.)

- Physics Stack Exchange discussion on particle number non-conservation. (Provides a clear example of how in QFT two particles can annihilate into one or one can produce many, illustrating non-conservation of a countable particle number.)

- Darwin, Charles. On the Origin of Species, 1859. (Noted that species are “arbitrary” delineations for our convenience, an analogy for how our physics categories might be arbitrary sections of a continuum.)

- Bohm, David. Wholeness and the Implicate Order, 1980. (Philosophical physics text arguing for an implicate order – a holistic underlying reality – from which the explicate order of particles and objects emerges.)

- Korzybski, Alfred. “A map is not the territory,” Science and Sanity, 1933. (A reminder that our descriptions and models are not to be confused with the reality they describe – highly pertinent to interpreting physical theories.)

Leave a comment