Defining Species – The Classical Concepts and Their Limits

Biologists and naturalists have long sought to define what a species is. Traditionally, several major species concepts have been used, each with its own criteria and limitations:

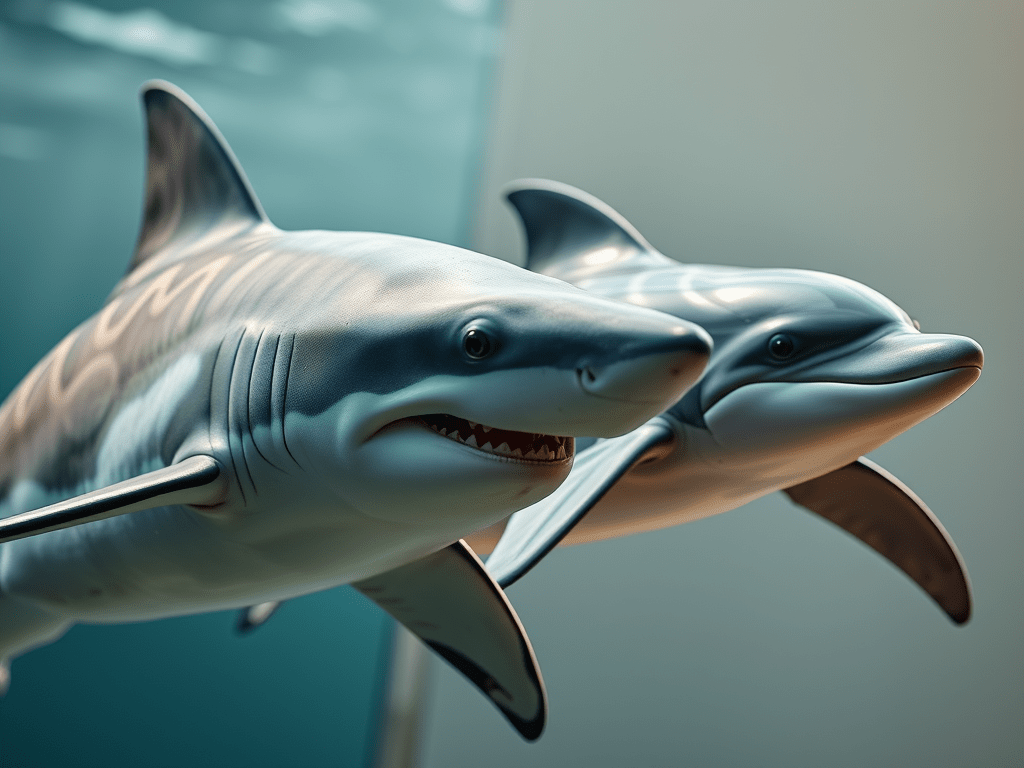

- Morphological Species Concept: Defines species based on distinct physical traits (morphology). If two organisms look sufficiently different in form or structure, they are classified as different species. This was the oldest practical approach – dating back to Linnaeus and earlier – and is still useful for fossil organisms or cases where other data (behavior, genetics) are unavailable. For example, paleontologists comparing fossil trilobites may only have shell morphology to go on. However, morphology can be misleading. Convergent evolution can make unrelated creatures look similar (consider a shark vs. a dolphin – outwardly alike, but one is a fish and the other a mammal). Conversely, members of the same species can vary wildly in appearance (due to sex, age, environment), and some distinct species are “cryptic” – nearly identical looking. Thus, a purely morphological definition often breaks down; it’s a convenient starting point but far from absolute.

- Biological Species Concept (BSC): Probably the most famous definition, championed by Ernst Mayr in 1942. Under BSC, a species is a group of organisms that can interbreed among themselves to produce fertile offspring, but are “reproductively isolated” from other such groups. In other words, members of a species recognize each other as potential mates and exchange genes, whereas they do not (successfully) breed with outsiders. This concept ties species to gene flow: species are gene pools separated by reproductive barriers. BSC is powerful for many animals and plants – for instance, Eastern and Western meadowlarks (two almost identical-looking birds in North America) do not interbreed in nature because they have different songs, so by BSC they are separate species. But the biological concept has notorious limitations. First, it only applies to organisms that reproduce sexually. It’s meaningless for bacteria (which reproduce asexually by splitting) or organisms that hybridize freely. Second, it can be impractical to test – if populations are geographically separated (allopatric), how do we know if they could interbreed? (We often can’t, without artificially trying.) Indeed, Mayr’s own contemporaries pointed out that strictly applying reproductive isolation as the criterion leaves many gray areas. Many clearly distinct species can hybridize under certain conditions (in captivity or in hybrid zones) yet remain separate in nature. And what do we do with fossils? We obviously can’t check who mated with whom in the Jurassic. In short, BSC defines an idealized boundary that nature often fails to respect.

- Phylogenetic (Lineage) Species Concept: A more modern approach defines a species as the smallest branch on the “tree of life” – essentially, a species is a population or group of populations that has evolved independently of others, forming a distinct lineage. In practice, the Phylogenetic Species Concept (PSC) often means identifying species by unique combinations of traits or genes that no other group has. If a cluster of organisms share a common ancestor and certain defining characteristics (genetic or morphological) not found outside the group, they can be deemed a species under PSC. This concept emphasizes diagnosable differences and monophyly (each species should be a single “branch” of related organisms). It’s very useful with DNA sequencing: even if two populations look alike, if their DNA shows consistent divergence, they might be split into separate species. PSC can often detect “cryptic species” that BSC or morphology would overlook. However, PSC can over-split in some cases – every minor genetic difference could be taken as evidence of a new species. Also, gene flow between species (via hybridization) complicates the picture of neat, separate branches. There are multiple versions of PSC, but all seek an objective, ancestry-based way to delimit species.

In addition to these, biologists have proposed ecological species concepts (focusing on unique ecological niches), evolutionary species concepts (defining species as lineages with their own evolutionary role and tendencies), and more. The very abundance of definitions is telling: there is no single, universally correct way to pinpoint where one species ends and another begins. In fact, the multitude of species concepts has given rise to what’s humorously called the “species problem” in biology – a recognition that “species” is a fuzzy concept. One scholar wryly noted that biologists have a “conceptual delicatessen” of species definitions to choose from, assembling a custom definition that suits the organisms they study. This pragmatic approach – picking whichever concept is most useful in context – is not a weakness of science but a reflection of a deeper truth: different organisms defy a single, tidy definition of species. As the Biology LibreText puts it, no matter what concept you use, “not all organisms are easily categorized into distinct groups” and species boundaries remain a dynamic, debated topic in evolutionary biology.

Why is it so hard to define species? The answer lies in how evolution actually works. All these concepts are human attempts to draw lines on a continuous process. Life doesn’t come with pre-attached labels. In Darwin’s words, “I was much struck how entirely vague and arbitrary is the distinction between species and varieties.”. Darwin, observing slight differences among birds on adjacent Galápagos islands, realized that there was no sharp break between what naturalists might call mere “varieties” and true “species” – it was a matter of degree. He concluded that “the term species” might ultimately be “an arbitrary distinction, a mere artificial combination made for convenience”, and that biologists would be “freed from the vain search for the undiscovered and undiscoverable essence of the term species.”. In other words, Darwin recognized that species have no special “essence” or clear starting point. They emerge gradually along evolutionary lineages. Modern evolutionary theory fully supports this: speciation is usually a gradual process, not a single moment. Populations diverge over time; at what point do they become “different species”? Any cutoff we choose is somewhat arbitrary.

To appreciate this, let’s examine some real-world cases where nature laughs at our neat definitions.

Nature’s Continuum: When Species Boundaries Break Down

Biologists often encounter organisms that challenge the notion of species as well-defined “boxes.” Evolution is a continuum, and sometimes we catch life in the act of diversification – the intermediate shades of an ongoing process. Here are a few edge cases that underscore how fuzzy species distinctions can be:

- Ring Species – The Circular Continuum: A ring species is a classic textbook paradox of the species concept. In a ring species, you have a chain of interbreeding populations that loop around geographically such that the populations at one end of the chain can no longer interbreed with those at the other end – despite a continuous series of gene flow in between. A famous example is the greenish warbler (Phylloscopus trochiloides) around the Tibetan Plateau. As these little birds expanded their range northward around the Himalayas, they formed a ring of populations. Neighboring populations interbreed, forming a gradual spectrum of variation – no two adjacent populations are fully reproductively isolated. But where the ring closes in Siberia, the birds that come from the west and the birds coming from the east meet – and do not recognize each other as mates. They coexist without interbreeding, behaving as distinct species. So, are they one species or two? According to the Biological Species Concept, the two end populations in Siberia are different species (since they won’t mate). Yet all along the ring, each group interbreeds with its neighbors, linking the two ends by a chain of gene flow. There is no clear breakpoint in the circle where one can say “here a new species arises” – the change is continuous. As one account describes it: “traits change gradually through this ring of populations. There is no place where there is an obvious species boundary… Hence the two distinct ‘species’ in Siberia are connected by gene flow.”. The warblers’ ring vividly illustrates that species distinctions can be a matter of perspective and scale. If some intermediate populations in the ring were to go extinct, the continuity would break and we’d cleanly have two species – which shows how arbitrary our labels can be. Other potential ring species include the Ensatina salamanders encircling California’s Central Valley, and the Larus gulls around the Arctic Circle (though these examples have complexities and debates of their own). The general point remains: ring species demonstrate that “species boundaries arise gradually and often exist on a continuum.”. What we call separate species today might have been connected by intermediates in the recent past.

- Hybrids and Gene Flow Across Species: A cornerstone of the biological species idea is reproductive isolation – yet in the real world, ostensibly separate species often aren’t completely isolated. Especially in plants, but also in animals, hybridization is surprisingly common. Distinct species can exchange genes through hybrid offspring, a process known as introgression. For example, many species of oak trees interbreed at their margins, blurring species lines. In waterfowl, ducks of different species hybridize not infrequently. Even humans carry a small percentage of genes from Neanderthals and other archaic humans – a testament that our own species had porous boundaries in the past. Modern genomic studies have revealed that “many distinct species maintain some level of gene flow”, exchanging genes despite being mostly separate. In fact, one research review bluntly stated: “species are not real in an evolutionary sense. They are man-made concepts… Some species are very distinct, others less so.”. There are cases of hybrid species arising when two different parent species merge their lineages (common in plants via polyploidy, but also known in fish and insects). All of this makes it clear that reproductive isolation is seldom black-and-white. Instead of absolute barriers, there are degrees of reproductive separation – and consequently, fuzzy boundaries. We often find “species complexes” or “syngameons” – groups of closely related species with ongoing gene flow. The Biological Species Concept struggles here: if two forms hybridize occasionally but usually don’t, are they one species or two? The answer can be somewhat subjective. Taxonomists must decide how much gene flow is “too much” to call things separate species, and different experts may draw the line differently. The more we learn (especially with DNA), the more we see “barriers of gene flow remain porous” across the tree of life. Species are generally cohesive, but not hermetically sealed units.

- Continuum of Differentiation: Speciation is a process that happens over time, and we sometimes see all its stages in a living group – from barely distinguishable populations to young species to ancient splits. Biologists speak of a “speciation continuum”. Consider an example like the Ensatina salamanders of California, which form a ring species: around the ring you can find every intermediate stage from full interbreeding to complete reproductive isolation. Or consider populations of fruit flies or finches on different islands, showing various degrees of divergence. There is often no moment of “speciation” – rather, populations gradually accumulate differences. With enough time and enough differentiation, they become “good species” by anyone’s definition. But in early stages, we often have “incipient species” – populations in the midst of splitting, where any species definition is debatable. Many biologists now favor the view that a species is essentially an evolving lineage – a segment of the population-lineage continuum where we decide to give a name. By that view, saying “species X and species Y” is like taking two snapshots along a continuum of time and labeling them. In practice, we tend to label the ends of the process, where differences are obvious and stable. But nature is full of those gray gradients in between.

- Paraphyletic and Misleading Taxonomic Groups: It’s not just the species level – even higher taxonomic groupings can misrepresent nature’s continuity. A striking example: the everyday category “fish.” Ask anyone what a fish is, and they can tell you – a gilled aquatic vertebrate. But evolutionary biology has revealed a surprise: there is no single coherent group of “fish” that includes all fish and nothing else. In fact, if you include all descendants of the first fishes, you end up including amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals as well! By excluding tetrapods, the traditional idea of “fish” cuts off an entire branch of descendants, rendering “fish” a paraphyletic group. As one source succinctly states: “Fishes are a paraphyletic group and for this reason, the class Pisces is no longer used in formal taxonomy.”. In plain terms, what we casually call fish doesn’t correspond to a single evolutionary unit – it’s an arbitrary slice of the tree of life. Similarly, “reptiles” traditionally excluded birds, making “Reptilia” paraphyletic unless birds are included. Even terms like “invertebrates” (meaning all animals except vertebrates) or “protists” (single-celled eukaryotes) are catch-all categories of convenience, not natural lineages. Another interesting case is the idea of a “tree.” You might think “trees” are a natural group, but biologically a “tree” is just a plant that grows wood and height – a growth form that has evolved in unrelated lineages (palms are trees, oaks are trees, tree ferns are “trees” – but these are vastly distant relatives). “Tree” is not a taxonomic unit at all, just a human description of form. These examples remind us that many of our everyday groupings are maps drawn by us, not necessarily reflections of how nature is fundamentally organized. The category of “fish” is convenient, but it’s taxonomically misleading if taken too rigidly – it obscures the fact that some fish are more closely related to us than to other “fish”! In essence, any rank above species (genus, family, etc.) is a human construct for our mental convenience. We decide how to group genera into families, for example – there’s no objective line in nature that says where “family” begins. Species are often treated as special (the basic units of biodiversity), but as we’re seeing, even species are squishy constructs in many cases.

The upshot of all these cases – rings, hybrids, clines, paraphyly – is a humbling and profound realization: nature is largely continuous. Life evolves gradually, and while distinct clusters (what we call species) do exist, they emerge from a backdrop of continuity. The boundaries are often blurry because evolution hasn’t read our textbooks. The living world shows “every imaginable gradation” from one form to another, reflecting the seamlessness of evolutionary change. We humans, however, are category-makers. We slice up the continuum into discrete bins because that’s how our brains handle complexity.

Taxonomy: The Map, Not the Territory

All classification schemes – the Linnaean taxonomy of Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species, or any other system – are ultimately maps we overlay on the biological world. They are immensely useful maps! They help us organize and communicate about the staggering diversity of life. But we must remember: the map is not the territory. The categories are not inherent in nature; we impose them for our convenience and cognitive needs.

Taxonomist and philosopher of science John Wilkins put it succinctly: biologists tailor their species concept to fit the evidence, rather than expecting nature to fit a single definition. In other words, our terms flex and adapt as we learn more – a hint that the terms are our tools, not nature’s intrinsic structure.

It’s helpful to draw an analogy: think of a color spectrum. We have names like red, orange, yellow, etc. But in a rainbow, where exactly does orange end and yellow begin? The spectrum is continuous wavelengths of light. The color names are convenient labels for parts of that continuum. Arguing about what is “truly yellow” vs “truly orange” is somewhat futile – the divisions are artificial, though useful for communication. In much the same way, evolution produces a spectrum of life forms and degrees of relatedness. Our species and genus names are like the color names – they chunk the spectrum into manageable units.

Philosophers have long grappled with whether species are “real” natural kinds or just nominal categories. In modern philosophy of biology, one influential view (Ghiselin and Hull) is that a species is not a class of things but an individual – a historical entity, like a long river that may branch and change course. In that view, asking for a strict definition of a species is like asking for a strict definition of “the Mississippi River” – you can describe it, but where it truly begins and ends (especially with changing deltas or bifurcations) can be arbitrary. Another perspective is that species are family resemblance concepts – most members share certain traits, but there isn’t a single essence.

Perhaps the most direct demonstration that taxonomy is a human construct is the constant flux in classification. Every year, taxonomists split or lump species, redefine genus boundaries, and rearrange groups based on new data. An animal that was considered one species may be split into two after closer study (because we found out they don’t interbreed, or their DNA is quite distinct). Conversely, what were thought to be separate species might get lumped into one if new evidence shows continuity. One cheeky paper title once noted: “Species are hypotheses”. Indeed, calling something a species is a hypothesis that a certain group of organisms is distinct in some meaningful way. And like any hypothesis, it can be revised with new information.

So, if nature doesn’t have neat lines, why do we see distinct species at all? One might wonder – if everything is continuous, how come we can usually tell a cat from a dog, or an oak tree from a pine? It turns out that while continuity is the rule over evolutionary time, processes in nature do produce clusters. Organisms tend to form relatively discrete units temporarily because of reproductive communities. Within a species, gene exchange keeps the group more or less coherent; once gene flow stops between two groups, they can drift apart and become more distinct. So in any given moment, life does appear in packages – “species” that are separate enough to notice. A snapshot of the present biosphere will show many clear species, just as a slice at one moment in a rainbow shows distinct colors to our eyes. As Stephen Jay Gould explained, a “momentary slice of any continuum looks tolerably discrete”. For example, living horse species are obviously distinct from living rhinos. But if you trace their lineages back, horses and rhinos share a common ancestor and a continuous series of intermediate forms – so where in that ancestry did “horse” begin and “non-horse” end? Gould notes the paradox that Darwin and Lamarck, who saw the continuity of life, still used species extensively in practice (e.g., Darwin spent years classifying barnacles into species). The reconciliation, Gould argued, is that evolution mostly happens by branching. When a lineage splits (speciation by splitting off an isolated population), you do get two lineages that thereafter don’t mix – an “objective” separation has occurred. Over time, that yields distinct species. However, during the formation of that branch, when it’s just starting, things are muddy. But because many species undergo long periods of stability after splitting (as in the theory of punctuated equilibrium), by the time we observe them, they often are well-differentiated clusters. Thus, the natural world at any given time can indeed be described as “separate and definable groups we call species” – but this should not fool us into thinking those groups have eternally fixed boundaries or Platonic essences.

Another way to put it: species (and other taxonomic ranks) are useful abstractions. They are like lines of latitude and longitude on a globe – we impose them for reference, and they help us navigate, but there’s no physical line on Earth at the Equator. Species names help us navigate the tree of life, but the tree itself is a seamless web of ancestry and descent.

There is also a cognitive side to this. Humans evolved to recognize patterns and group things – it’s essential for survival (knowing which plants are edible, which animals are dangerous, etc.). Our brains like categories. We label things with nouns, we think in either/or terms (“is it A or B?”). The living world, however, is under no obligation to fit our language cleanly. We experience a kind of mental discomfort when confronted with ambiguity. The naturalist who crosses an arbitrary geographic boundary and notices nothing abruptly changes (like Gould’s quip about crossing a state line and the scenery being the same) feels the mismatch between mental categories and reality’s continuum. As Gould humorously noted, saying “Idaho doesn’t look different from Washington” is akin to people assuming species boundaries are like state lines on a map. But those borders are our own constructs. Much of nature “is continuous, but our mental structures require divisions and categories.”. Taxonomy is our attempt to divide up “continuous real estate” into states and countries. It’s a map for the “territory” of biodiversity.

A striking illustration is in cases of individuality and connectedness. We usually have an intuition for what a single organism is – one dog, one tree. But even this can blur at the edges. Is a clonal grove of aspen trees, where thousands of trunks are connected by one root network, many individuals or one “super-organism”? What about coral reefs composed of countless polyps, or a colony of ants – is the colony an integrated organism in itself? Philosophers and biologists puzzle over the definition of an individual. In the 19th century, some naturalists realized that a “tree” can be viewed as a colony of buds (each capable of becoming a new plant). Charles Darwin marveled at “compound animals” like corals, where “the individuality of each is not yet completed” – a colony of polyps can behave like a single organism. These examples drive home a parallel message: just as species are fuzzy sets of organisms, an organism itself can be a fuzzy set of component life forms. (Consider that you are an assemblage of human cells plus a vast microbiome of bacteria – a holobiont – and you can’t live without your microbial partners. What, then, is the boundary of “you” as a biological individual?) In short, at every level, life resists rigid boundaries. The concept of a neatly bounded self or species is a useful fiction that breaks down when examined closely. Life is a spectrum and a network, not a bunch of isolated boxes.

Evolution, Continuity, and the Myth of “Fixed Kinds”

Why does this matter beyond academic debates? One important reason is that misunderstanding species can fuel anti-evolution arguments, particularly from creationist or “intelligent design” camps. For a long time, opponents of evolution insisted that species were fixed and unchangeable – “each species is after its kind,” as per a literal reading of Genesis. Early creationists equated species with the created “kinds” mentioned in scripture, believing no new species had ever appeared. This idea of immutable species was actually mainstream in biology before Darwin. Darwin’s work shattered that notion by showing that species are not fixed – they arise from other species.

Interestingly, many modern creationists have adjusted their stance: they often concede that some speciation happens (to account for biodiversity emerging from the few “kinds” aboard Noah’s Ark, for example), but they maintain that evolution has limits. They say “microevolution” (variation within a “kind”) is possible, but “macroevolution” (one “kind” turning into another) is not. In effect, they’ve invented a perhaps larger, vaguer box – the “created kind” (often equated to something like a genus or family) – and claim that box is inviolable. But this simply shifts the problem. They still assume somewhere there are hard boundaries that evolution cannot cross. Creationist literature uses terms like “baramin” (created kind) and employs hybridization tests to decide what belongs in the same kind. For instance, creationists might say all cats (from house cats to lions) are one kind, and all dogs, wolves, and coyotes are another – because cats won’t hybridize with dogs, etc. Yet even in their framework, the boundaries are fuzzy and empirical. One creationist, Frank Marsh, suggested that if you can hybridize two creatures (even via intermediates), they’re of the same “basic type”. This is essentially the Biological Species Concept writ large. And guess what? They ran into the same continuum issue. As one analysis notes: “Creationists do not have an exact definition of the original created kind for the same reasons that taxonomists cannot precisely define species: every imaginable gradation between species exists.”. In other words, they discovered exactly what we’ve been exploring – there is a continuum of life. In trying to allow “microevolution” but disallow “new kinds,” they’ve put their finger on the fact that drawing a line is arbitrary. If dogs, wolves, and foxes are all one kind (because of some gene flow or similarity), what about foxes and other canids? What about canids and bears at a further remove? So-called “baraminologists” have to subjectively decide where to stop grouping organisms as related. They often rely on a mix of morphological similarity and hybridization data – ironically, using the same evidence evolutionists use, but then asserting a non-evolutionary interpretation.

Creationist arguments often betray an essentialist mindset: they imagine species (or kinds) have fixed “essences,” and evolution must somehow violate those essences to create a truly new type of organism. But as we’ve seen, there are no essences – there are just populations of organisms accumulating changes over time. There’s no invisible barrier that says, for example, a descendant of the dog kind cannot eventually, after millions of years and many changes, look nothing like a “dog” anymore. Indeed, creationists themselves implicitly accept major change – they often claim all extant cats (lions, tigers, cougars, domestic cats, etc.) diversified from a single pair on the Ark in only a few thousand years. That’s rapid evolution by any measure! But they halt it arbitrarily at a “family” level, insisting, for instance, that cats always remain cats. However, “cat” is a human label. If we went back 30 million years, the common ancestor of cats and hyenas would probably just be called a cat-like mammal – was that a cat or not? The question is moot; it was an ancestor that gave rise to branches, one of which became modern cats, another hyenas. Over enough time, small differences compound into big differences. The difference between micro- and macro-evolution is scale and accumulation, not kind. There is no magical jump or new ingredient that macroevolution requires – it’s microevolution plus time.

By clinging to the notion that species are clear-cut and unchanging, creationist arguments set up a false expectation: “Show me a dog turning into a non-dog,” or the infamous “if evolution is true, why are there still apes?” These challenges stem from treating labels as absolute. Evolution predicts – and the fossil record confirms – that lineages split and diverge gradually. You won’t see a cow give birth to a horse; what you see are populations slowly shifting, and eventually our retrospective labeling changes. The ape question is answered by understanding branching: humans didn’t evolve from the modern apes we see today; humans and apes evolved from a common ancestor. The ancestor’s descendants branched into multiple lineages – some became today’s chimpanzees, some became humans, etc. The ancestor was neither chimp nor human by our definitions, but over time, branches yielded the distinct forms. If you insist on hard categories, it seems paradoxical; once you see categories as fluid, it makes sense.

In short, creationist objections to speciation often boil down to a category error – treating “species” or “kinds” as if they were eternally separate like chess pieces, rather than labels we slap on a segment of an evolutionary continuum. When they say “no new information can arise” or “one kind can’t turn into another,” they are picturing a static world that doesn’t exist. The biological reality is that everything is interconnected and change is constant – which is exactly what evolutionary theory describes. By highlighting the continuity of life and the arbitrariness of species boundaries, we can show that creationist arguments are attacking a straw man. Evolution doesn’t require a fish to sprout legs overnight or a dog to give birth to a cat. It only requires that over long spans, populations diverge, and that our classification at some point deems them separate species. And indeed, we have observed speciation in action in many organisms (especially fast-breeding ones like insects, plants, and microbes). But even if one hadn’t personally seen a species split, the continuous variation and the ring species type scenarios demonstrate that nature doesn’t have rigid walls between “kinds.” Given enough gradation, the endpoints of a continuum can be dramatically different (just as the ends of the warbler ring are effectively different species).

Embracing the Continuum of Life

If we fully embrace that species and other taxonomic ranks are human abstractions – incredibly useful, but abstractions nonetheless – it can profoundly reshape how we view life. Rather than a static “Great Chain of Being” or a fixed inventory of created types, we see life as a flowing, branching river. Every species is a snapshot of an ongoing story. Every individual organism is a temporary expression of a genome that was inherited and will perhaps be passed on with modifications. The Tree of Life is really more of a sprawling, dynamic web – with branches touching (through gene flow) and sometimes recombining, with no clear beginning or end to any “kind.”

This perspective is both humbling and enlightening. It dissolves the illusion of human exceptionalism to some degree – we too are part of this continuum, one twig on the vast tree. There is no fine line where “animal” ends and “human” begins; we just define things that way for convenience. In fact, when you line up all intermediate ancestors, categories like fish, reptile, mammal, primate, etc., become waypoints, not hard borders. Recognizing this continuity can foster a sense of kinship with all life. The differences we emphasize are recent, superficial twigs on a colossal oak of evolution. At the genetic level, we share a large proportion of our genes not just with apes, but even with mice, flies, and yeast. Those similarities reflect common ancestry – the continuity of life’s biochemical heritage.

Letting go of strict categories also encourages us to appreciate diversity without pigeonholing. We can still use the concept of species – it’s practical – but we understand its fluidity. In conservation biology, this is crucial. We protect “endangered species,” but what are we really protecting? Not an immutable kind, but a unique, irreplaceable lineage – a node on the tree that, if lost, cannot be regained. It’s like losing a language or a branch of human culture; something continuous with the rest of life but distinct in its history disappears. Thinking in terms of lineages and gene pools, rather than fixed essences, also helps in issues like conservation units, recognizing that hybridization (often viewed negatively under a strict species concept) can be part of natural evolutionary rescue and adaptation.

Philosophically, accepting biological continuity can be mind-expanding. It challenges our deeply held notions of identity. We tend to think in terms of “self” versus “other,” “us” versus “them,” neatly defined units. Biology shows that these lines can be arbitrary. On a genetic level, you are a mosaic of your ancestors; on an evolutionary level, Homo sapiens is a temporary name for an ongoing lineage that used to be something else and will become something else. Even the concept of a “tree” as a distinct object can be blurred if that tree can clone itself or fuse roots with another. It invites almost a Zen-like insight that boundaries in nature are often illusions of perspective. At a distance, you see separate dots; zoom in, and you find they connect.

This doesn’t mean distinctions aren’t real or useful at a given scale. It means they are emergent. Species are emergent patterns – clusters of similarity and gene flow in the fabric of life. They’re like eddies in a stream: you can point to an eddy, describe it, even give it a name, but it’s part of the flowing water and will eventually dissipate or morph into something else.

In evolutionary terms, every species will either go extinct or evolve into new species (or, usually, both – since if it evolves, the original form ceases to be, effectively). Thus, long-term, there are no permanent entities, only lineages in flux. Embracing that can change how one thinks about biodiversity: not as a static collection of items to catalog, but as a dynamic, ever-changing tapestry. Our taxonomies are snapshots of that tapestry in the current era.

It’s fascinating that modern genomic research even blurs the concept of a single “Tree of Life” at the base – with discoveries of horizontal gene transfer among early life forms (and still among microbes), the tree has networks and loops. It’s as if even at the deepest level, lineage separation wasn’t absolute; branches could fuse or share information. Life may be better represented as a web or a braided river.

For a science-curious audience, these ideas can be thrilling, if a bit unsettling. They encourage us to think in terms of systems and processes rather than fixed categories. It’s a shift from a noun-based view of biology (each species a noun) to a verb-based view – life as “verbing”, always doing, changing, becoming. As the philosopher Heraclitus said, you can’t step in the same river twice – and indeed, you can’t encounter the “same” species over geological time, because it’s always either changing or going extinct.

This fluid view of life does not weaken evolutionary theory – on the contrary, it is evolutionary theory. It dispels the misconceptions and shows evolution’s true genius: tremendous, unbroken continuity producing apparent discontinuities that we label as species and higher taxa. It’s evolution’s gradualness that fools us into thinking in separate kinds, much like a slow gradation of color fools us into seeing distinct bands.

To conclude, recognizing species and all taxonomic ranks as human-imposed abstractions on a continuous process is liberating. It frees us from the tyranny of the discrete. It allows us to better rebut anti-evolution arguments that hinge on false dichotomies and fixed “kinds.” It gives us a deeper appreciation for the subtlety of natural change. Yes, we will still talk about species – we must, to communicate. But we’ll do so with a wink and nod to Darwin’s insight that it’s an “arbitrary distinction” made for convenience. The map is useful, but we won’t mistake it for the territory. And when we gaze at the living world – from the greenish warblers circling the Himalayas, to the hybridizing oaks, to the strange colonial jellyfish that blur individual and collective – we can appreciate that nature transcends the neat little boxes we try to put it in. Life is far more fluid, interconnected, and continuous – and that, in its own way, is even more awe-inspiring than a perfectly catalogued ark of unchanging species. It means every creature is a cousin; every boundary is an opportunity to learn how nature builds diversity without lines in the sand. Embracing that continuity enriches our understanding of evolution and deepens our reverence for the truly remarkable story that life on Earth tells – a story not of separate chapters, but of one grand, unbroken narrative still unfolding.

Sources:

- Darwin, C. (1859). On the Origin of Species – noted the arbitrary distinction between species and varieties.

- Irwin, D. et al. (University of British Columbia). Greenish Warbler ring species description.

- Wikipedia: Species – discussion of species concepts and fuzzy boundaries (hybridization, ring species, asexual organisms).

- Wikipedia: Ring species – explanation of how ring species illustrate gradual emergence of species boundaries.

- Wilkins, J. (2006). “Species, Kinds, and Evolution.” Reports of NCSE 26(4) – history of species concept, multiple definitions (“conceptual delicatessen”).

- Biology LibreTexts (2025). “Species Concepts” – definitions of Biological, Morphological, Lineage concepts and their limitations.

- Jody Hey (2009). Why Should We Care About Species? – highlights Darwin’s view on species continuity and the species problem.

- Wikipedia: Taxonomy of fish – notes that “fish” is a paraphyletic (incomplete) grouping, not a single true clade.

- NCSE (1980s). “Defining Kinds” – discusses creationist concepts of “created kinds” and the inherent gradation problem.

- ResearchGate discussion (2017). “Why do many of us still think that species are real?” – evolutionary biologists noting species are man-made categories on nature’s continuum.

- Gould, S. J. (1992). “What Is a Species?” Discover Magazine – explores the reality of species, quoting Darwin/Lamarck and explaining evolutionary branching vs continuum.

- Aeon Essays (2020). “What is an individual?” – discusses blurred individuality in colonial organisms (Erasmus Darwin’s tree-as-colony idea, Charles Darwin on compound animals).

Leave a comment