How a colony of hardy microbes, pulsing with faint light, might help crack the riddle of dark matter

A New Kind of Detector

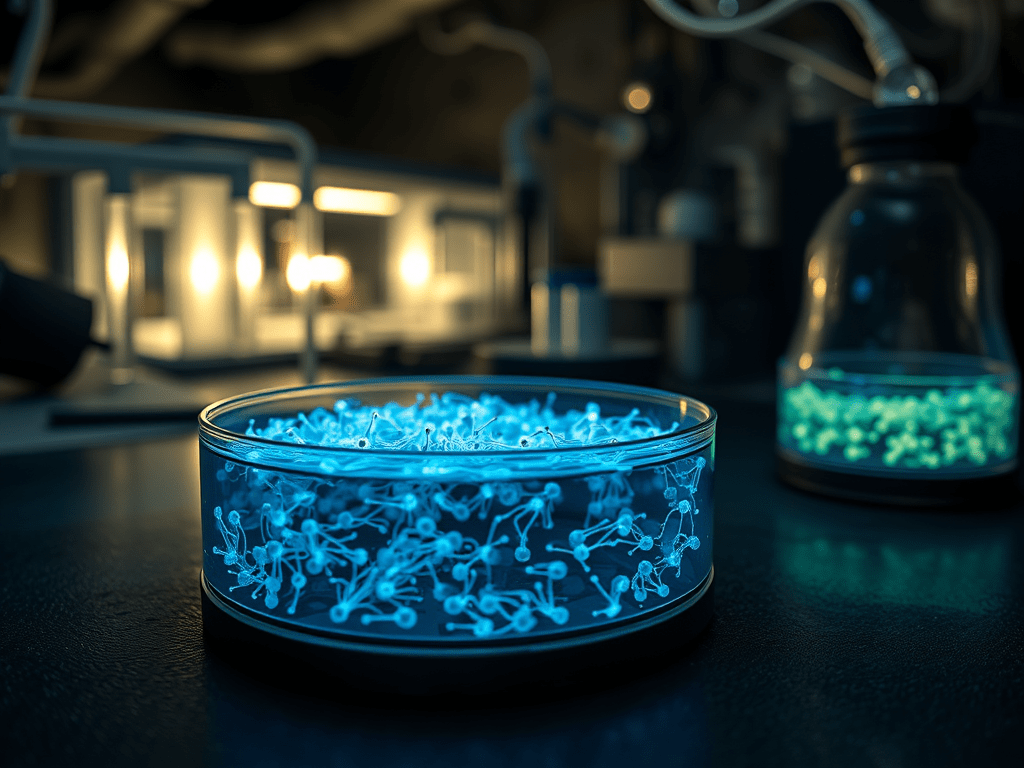

Two kilometres beneath the Canadian Shield, physicists share their lab space with something unexpected: petri dishes. Not the usual kind, either, but cultures of deep-mine bacteria that whisper photons—so faint you need ultrasensitive cameras to notice. A growing band of researchers thinks those flickers could become a biological early-warning system for the most elusive stuff in the cosmos: dark matter.

Dark matter is the invisible gravitational glue that outweighs all the stars and gas we can see; yet after decades of heroic underground experiments, the leading suspects—so-called WIMPs, or Weakly Interacting Massive Particles—have slipped through every net. What if, instead of ever-bigger vats of liquid xenon cooled to -100 °C, the solution were… a living organism?

Why Bacteria Glow at All

Most life forms, humans included, leak a trickle of “biophotons.” It happens when metabolic stress creates reactive oxygen species—chemical bullies that leave certain molecules in an excited state. As those molecules relax, they throw off single photons in the near-ultraviolet and blue. The glow is a billion times dimmer than a firefly, but it’s real.

Now imagine a WIMP barreling through a bacterium. Theory says the particle would deposit a few thousand electronvolts of energy—tiny by nuclear-physics standards, but hefty compared to the usual biochemical bumps and bruises. If that energy spawns extra oxygen radicals, the bacterial glow should brighten ever so slightly. Life itself becomes the amplifier.

The Underground Bioreactor

The flagship proposal centres on Bacillus subterraneus—a spore-forming microbe found 2.4 km beneath South Africa’s gold fields. It thrives under pressure, survives meagre rations, and keeps glowing at refrigerator temperatures. Scientists would suspend a kilogram of these cells in clear agar, seal them in a quartz cylinder, and line the walls with a mosaic of silicon photomultipliers—digital eyes that can spot single photons.

Why bury the experiment deep underground at SNOLAB? To escape the hail of cosmic-ray muons that pummel the surface and would swamp the subtle WIMP signal. The lab’s rock overburden cuts that background by a factor of ten million.

A twin setup on the surface acts as a control. If both cultures brighten and dim together, blame biology. If only the underground colony shows a yearly rhythm—peaking around early June, when Earth’s orbital motion adds to the “wind” of dark matter—it could be the long-sought signature physicists crave.

Crunching the Numbers

Early simulations paint a tantalising picture. For a 10 GeV WIMP (a popular mass range) and a quart-sized culture, the team expects roughly one recoil event per day. Each would unleash a burst of a few dozen extra photons. Multiply that by months and years of continuous monitoring, and a genuine dark-matter modulation might stand out above the bacterial noise with five-sigma certainty—the gold standard in physics—after three years.

Hurdles on the Road to Discovery

- Metabolic Mood Swings

Real microbes grow, age, mutate, and sometimes sulk. Researchers will log temperature, pH, nutrients, and oxygen around the clock—and periodically sequence the DNA—to make sure the culture itself isn’t introducing fake signals. - Photon “Snow”

Even cooled photomultipliers generate dark counts. The detectors must be characterised with obsessive care so no one mistakes electronic blips for biophotons. - Skepticism (and Funding)

Biology and particle physics rarely mix budgets. Grant panels will want assurance that the living detector is more than a whimsical side quest.

Why Bother?

If the microbes do spot dark matter, the payoff is enormous: confirmation of a new particle species, plus a novel, room-temperature sensor that complements massive cryogenic apparatus. If they don’t, the null result still tightens the net around WIMPs and teaches us about life under radiation stress—useful for planning missions to Europa or Mars.

Either way, the experiment reminds us that nature is versatile. Where human-built crystals and liquids have failed so far, perhaps a humble bacterium—glimmering softly in the dark—will finish the hunt.

Leave a comment